The Science Behind

You Map

Read time: 10 min

You Map’s foundations are built on a concept and field of study from neuroscience and psychology: interoception. Interoception is often described as a “hidden” sense. It’s our ability to perceive internal signals from the body. In this article, we explain what interoception is, how researchers study it, what science says about its connection to mental health and well-being, and how we draw on this science to make interoception accessible as a daily tool.

Main points in 60 seconds:

-

Interoception is your brain’s sense of internal signals like heart/respiratory rate, pain, or hunger and how it responds to those signals (often with emotion).

-

Scientists have studied this inner sense since the 1980s through simple means like gauging how accurately someone can count their heartbeats without checking their own pulse as well as using wearable sensors and MRIs.

-

Growing evidence suggests interoception plays critical roles in emotional regulation, empathy, and even your sense of self identity.

-

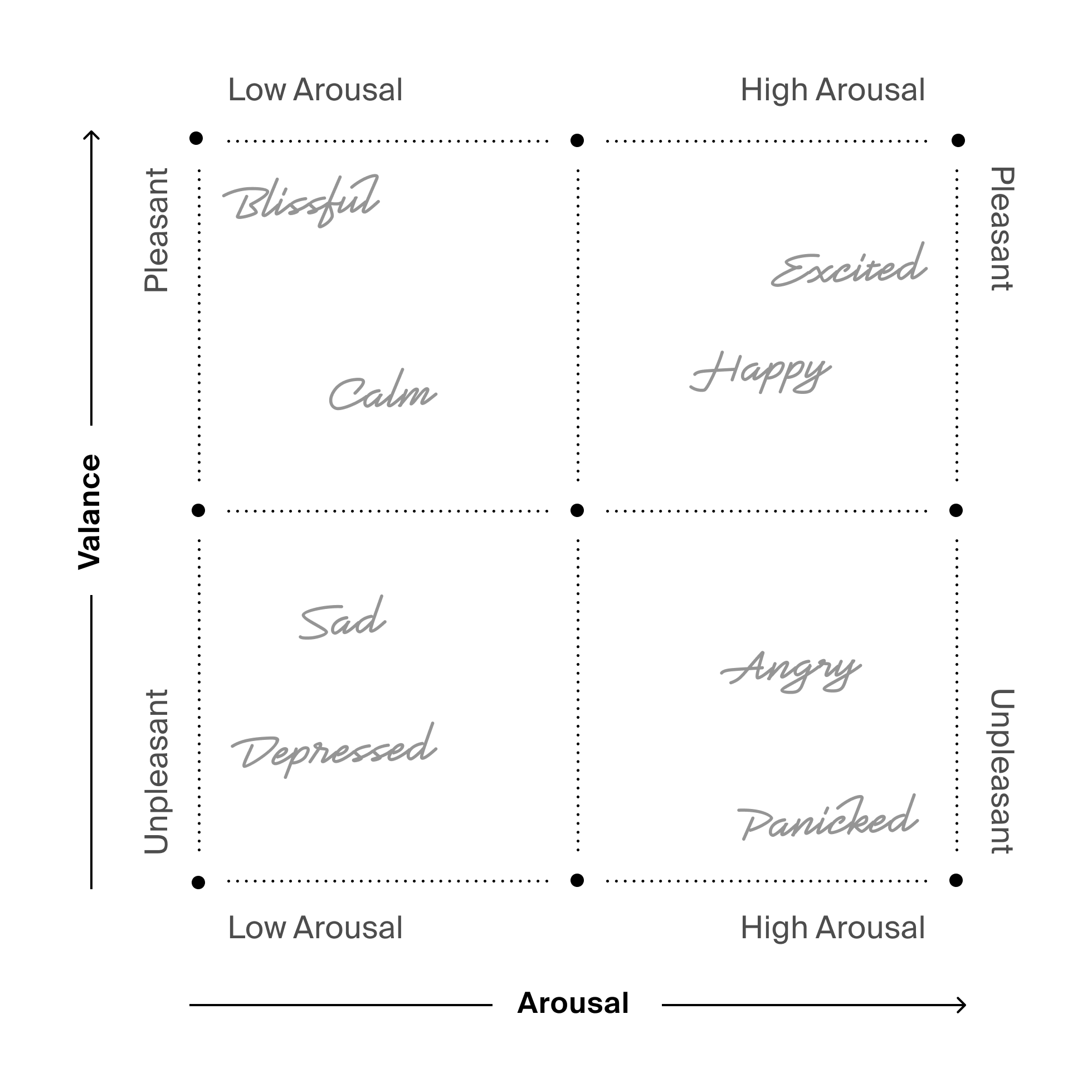

Researchers plot interoceptive sense using a simple diagram with arousal (the level or stimulation, energy, or intensity of an inner sensation) on one axis and valence (how comfortable or pleasant the inner signal is) on the other axis, which then roughly maps emotions into quadrants.

-

You Map brings greater structure, rigor, and extensibility to this interoceptive diagram whilst enhancing clarity, accessibility, and daily usefulness to create a tool for all to help them sharpen their interoceptive senses and thus boost emotional regulation, empathy, and sense of self identity.

What Is Interoception?

Interoception is a sense like touch, taste, or smell. But, where those are external, interoception is all about sensing the internal state of your body. Just as your eyes and ears track the outside world, interoception lets your brain track what’s happening inside you.

This includes feeling your heartbeat, hunger and fullness, your breath, your body temperature, pain, or even the sensation of your bladder being full.

These inner sensations form a continuous mental and emotional commentary on how your body is doing and help keep your body in homeostasis or balance.

Scientists consider interoception a foundation for our emotions and sense of self.

Signals from inside the body are integrated in the brain (notably in a region called the insular cortex) to create our conscious feeling of being in a body. The insula links internal signals, like a racing heart or queasy stomach, with emotions and self-awareness.

This brain integration is why interoception informs not just basic needs (thirst, pain, etc.) but also complex feelings. If you've ever felt “butterflies” in your stomach from anxiety or a warm calm feeling in your chest when happy, that's interoception at work.

Jump to Further Reading to learn more from Harvard Medicine & Scientific American

How Do Scientists Study Our Inner Sense?

A classic example of interoceptive studies is the heartbeat detection test. In the early 1980s, psychologist Rainer Schandry asked volunteers to silently count their own heartbeats (without checking their pulse) over brief periods. This became a go-to method to gauge interoceptive accuracy through today.

In some versions of this test, like with University of Sussex neuroscientist Hugo Critchley and team, researchers play a series of tones and ask participants whether the tones are in sync with their heartbeat, all while brain activity is recorded in an MRI scanner.

These experiments show that specific brain areas, especially the insula, become active when we focus on internal signals.

Researchers also use surveys and biofeedback devices to study interoception. For instance, questionnaires ask people to rate how strongly they feel internal sensations like hunger or stress. Wearable sensors can track subtle changes (like slight heart rate fluctuations or skin sweat) and compare them to a person’s self-reports.

All these methods help scientists quantify interoceptive awareness and understand how it varies between individuals.

Jump to Further Reading to learn more from Harvard Medicine & Scientific American

Interoception, Mental Health, and Well-Being

Evidence is mounting that our internal sensing system is integral to keeping the body and mind in balance, and that disturbances in interoception accompany many mental health conditions. When our brain has trouble interpreting internal signals, it can contribute to problems like anxiety, depression, or disordered eating.

Studies led by researchers like Sarah Garfinkel and Wolfgang Mehling have reported that individuals with depression, autism spectrum disorder, or anorexia nervosa often score lower on heartbeat perception tests than healthy individuals.

In eating disorders, patients may struggle to recognize hunger and fullness signals, and in depression there can be a numbness to internal feelings. The famous psychologist Oliver Sachs once noted patients who “lose touch” with internal sensations can feel alienated from their own bodies, a hallmark in certain trauma and dissociative disorders.

Encouragingly, research indicates that interoceptive awareness is a skill you can improve, and doing so may improve mental well-being.

Neuroscientists and psychologists have been testing interventions from traditional practices like mindfulness meditation and yoga to modern biofeedback devices. One study led by psychologist Norman Farb at the University of Toronto found that after several months of yoga training that emphasized noticing internal sensations, participants showed enhanced attention and became more confident about sensing their inner bodily states.

Other experiments have shown that people who undergo mindfulness-based therapy can increase activity in brain regions associated with interoception, and this correlates with reduced anxiety and depression symptoms.

In a 2022 clinical study on depression treatment, patients who had lower brain response to internal sensations (almost a “shutting down” of body awareness under stress) were eight times more likely to relapse into depression, whereas those who maintained sensory awareness were more resilient.

The good news is that with practice, the brain can learn to pay more attention to the body’s cues, potentially breaking cycles of negative emotion and there’s even evidence that sharpening interoception doesn’t just help one’s own mood.

Pioneering work by Prof. Hugo Critchley and Dr. Sarah Garfinkel has shown that people who are better at sensing their own internal signals tend to score higher in empathy and emotional understanding of others.

Being “in tune” with yourself may help you be more in tune with the feelings of people around you. Greater social connectedness and support, in turn, are well-known boosters of mental health and resilience. With this, a beneficial reinforcing feedback loop can take hold and growth can compound.

Jump to Further Reading to learn more from Harvard Medicine & Scientific American

How You Map Builds on Interoception Science

Understanding the science of interoception has direct practical benefits – and this is where You Map comes in. We developed You Map as a simple, everyday tool to help people apply these research insights to their own lives.

You Map is built on the same idea scientists use to study emotions: mapping how you feel along two key dimensions of internal state. One dimension is arousal, which ranges from low energy (calm or fatigued) to high energy (alert or activated). The other is valence, which ranges from very unpleasant feelings to very pleasant feelings.

This two-axis model (often called the arousal–valence model in affective science) is a way researchers represent emotions and bodily states in a chart. We’ve extended this proven framework to create an accessible self-reflection tool.

FIG 1. The traditional quadrant structure used for mapping emotions based on interoceptive sense via the arousal-valance model.

Using You Map involves pausing to tune into your body and emotions, then plotting your current state on a simple map of arousal and valence. For example, if you feel jittery and stressed, you might mark a point that’s high arousal and negative valence; if you feel relaxed and content, that’s low arousal and positive valence.

You Map builds on the scientific finding that self-awareness of internal signals can be improved with practice and structure. Just as researchers have participants pay attention to their heartbeat or breath in lab studies, You Map encourages you to regularly pay attention to what your body is telling you.

Over time, check-ins with You Map as a daily habit can strengthen your interoceptive awareness.

Our own research and testing has shown that as you become more adept at recognizing “Hey, my body is tense and my mood is low” or “I feel energized and clear-headed right now,” you gain an opportunity to respond productively. Your sharper inner-sense helps you deploy calming techniques, seek social support, and/or simply appreciate a good moment before emotions have time to take control.

We designed You Map to bridge the gap between cutting-edge interoception research and everyday life. It’s not about medical treatment or selling a cure, but about empowering you with an evidence-based way to reflect on your inner state and navigate your well-being with greater insight.

Further Reading

“Making Sense of Interoception” – Molly McDonough (Harvard Medical School, 2024)

A feature article explaining what interoception is and why it matters. It covers recent research at Harvard on how internal organ signals (heart, gut, etc.) influence the brain, and discusses conditions like anxiety, addiction, and chronic pain in the context of interoception. Readers will gain an overview of both the clinical significance and the cutting-edge biology of interoceptive sensations.

Read the article on Harvard Medicine

“We’ve Lost Touch with Our Bodies” – David Plans (Scientific American, 2019)

An accessible opinion piece that argues modern life has dulled our interoceptive awareness. The author (a scientist and entrepreneur) describes how disrupted interoception is linked to mental health issues like anxiety, mood disorders, eating disorders, and addiction. This article also touches on the history of interoception research and suggests how technology and mindfulness might help us regain body awareness.

Read the article on Scientific American

“A Broken Sense of Self Underlies Eating Disorders” – Carrie Arnold (Scientific American, 2012)

This article delves into the role of interoception in anorexia and body image disorders. It tells the story of a woman with anorexia who had difficulty sensing when she was cold or tired, illustrating interoceptive dysfunction. The piece explains how our brain’s insula integrates internal signals to form body awareness and how a simple heartbeat-counting test can reveal interoceptive acuity. Readers will learn how deficits in interoception can distort body image and emotion, and how scientists like Dr. Hugo Critchley measure this internal sense.

Read the article on Scientific American

“Where Mind and Body Meet” – Matthew Blakeslee & Sandra Blakeslee (Scientific American, 2007)

A deeper look into the neuroscience of interoception and emotion. This article highlights Hugo Critchley’s research linking heartbeat perception skill to activation in the brain’s insula and to empathy levels. It provides a clear explanation of how internal sensations are mapped in the brain and why this matters for our emotional life. It’s a great read for understanding the neural basis of the mind-body connection.

Read the article on Scientific American

“Paying Attention to Sensations Can Help Reset the Mind” – Norman Farb & Zindel Segal (Scientific American, 2024)

A recent piece by two psychology researchers demonstrating how training interoception can improve mental health. It discusses studies where practices like mindfulness meditation and interoceptive-focused yoga led to better emotional outcomes, such as lower risk of depression relapse. This article is practical in tone, reinforcing the idea that tuning into the “wilderness within” – our bodily sensations – can break negative habits and boost well-being.

Read the article on Scientific American